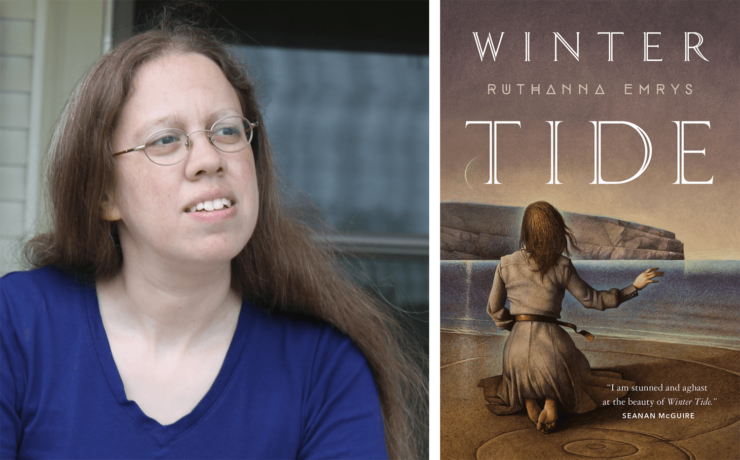

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of The Innsmouth Legacy series, including the short story “The Litany of Earth” and the novels Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her most recent work of short fiction is “Dinosaur, Roc, Peacock, Sparrow,” published as part of Jo Walton’s The Decameron Project. And she’s the co-host of Tor.com’s Lovecraft Reread with Anne M. Pillsworth.

Recently, she dropped by r/Fantasy for an AMA to talk about everything from writers who interrogate the racism and xenophobia in Lovecraft’s stories, to how to make Cthulhu sympathetic, to favorite cryptids. Head below for the highlights!

[Editor’s note: Questions and responses may have been edited for length and clarity.]

Besides your own stories, do you have any recommendations for Lovecraftian horror/fantasy that similarly defies or interrogates the xenophobia and racism in Lovecraft’s original stories?

I’ve mentioned Sonya Taaffe’s “All Our Salt-Bottled Hearts,” which is the other Jewish Deep One diaspora story and absolutely brilliant. I love Victor LaValle’s The Ballad of Black Tom, which plays with Lovecraft’s ultra-bigoted “Horror at Red Hook.” Gemma Files’s “Hairwork” does the same for “Medusa’s Coil” (which is Lovecraft’s most bigoted collaborative story and gives “Red Hook” a run for its money). Premee Mohamed’s “The Adventurer’s Wife,” Ng Yi-Shen’s “Xingzhou,” and most of Nadia Bulkin’s stories more generally do cool things with decolonizing the weird.

Any recommendations for other weird authors?

So many! Among the earlier authors, I adore Robert Chambers’ “King in Yellow” stories, which are brain-breaking razor-sharp satire—Robin Laws has done some cool things with that setting more recently. Modern authors: Sonya Taaffe wrote my favorite Deep One story (“All Our Salt-Bottled Hearts”), along with much excellent weird poetry and horror. Livia Llewellyn writes stories that are terrifying and also Not Even Remotely Safe for Work. I read my first Fiona Maeve Geist story recently and desperately want more. And I always keep an eye out for John Langan, Nadia Bulkin, Nibedita Sen, Mira Grant… the fundamental problem with having spent almost 6 years on a weird fiction blogging series is that I could give a very long answer to this question! For a good sample, though, my three favorite recent anthologies have been Robert S. Wilson’s Ashes and Entropy, Lynne Jamneck’s Dreams From the Witch House, and the Vandermeers’ The Weird.

How do you walk the line in Weird Fiction between doing your own thing, standing out in a crowded field, and sticking to the conventions of the genre?

I tend to write stories in conversation (or more often in argument) with other stories and authors. Sometimes that means playing directly with someone else’s worldbuilding—Winter Tide is meant to work on its own, but some of what I’m saying to/about Lovecraft depends on using his recognizable creations. But sometimes I just take a trope and run with it (off in a different direction, over a cliff)–“The Word of Flesh and Soul” is as much about academia and who gets the privilege of discovery as it is about The Language That Drives Men Mad, and using a specific pre-existing language would have put the story’s boundaries in the wrong place.

Buy the Book

Winter Tide

So how exactly does one make the Great Old One Cthulhu and his followers sympathetic?

So I should start out by saying that I do, in fact, enjoy Lovecraft’s writing and the original Mythos stories. I love the aliens entirely unthethered to humanoid norms, and the wild tempo of the language, and idea of a universe to which humans and all our problems are a footnote. But much like a Lovecraft protagonist, I’m both attracted to and repelled by his worlds. I find it impossible to ignore the extremely human bigotry at the core of it all—the fact that Lovecraft was so good at writing a world beyond human comprehension in part because his own world—his own ideas of who, in a just world, would matter and be important—were so small. And I also can’t help but notice that he describes his fictional monsters using the same language that he uses, in his letters, to describe the horror of hearing my ancestors speaking Yiddish on the streets of New York City. Or that Cthulhu and the other Mythosian deities are consistently worshipped by the powerless and oppressed.

Or that “The Shadow Over Innsmouth” starts with the people of Innsmouth getting sent to concentration camps, and that Lovecraft thinks this is a good thing.

But Lovecraft did write well enough, with enough power behind the “attraction” side of that attraction-repulsion dynamic, that I found it easy—necessary, even—to think about what the world would look like to people in (and after) those camps. I was also interested in characters who wouldn’t all react the same way to the core truths of cosmic horror. For those who don’t actually run things, the idea that you’re not the center of the universe isn’t a paradigm-breaking shock. So how do you handle the vastness of the universe and the smallness of your own perspective, when it’s not a dreadful revelation but everyday reality?

There are still horrors in my version, and only some of them are human. But there are also a lot more kinds of people worth talking to.

Can you tell us about Aeonism, the religion you made for the Deep Ones?

Secretly, I’m just a person who makes up religions, and have been ever since I read Vonnegutt’s Cat’s Cradle in high school.

Aeonism is meant to be a religion that takes comfort in the same things I find weirdly optimistic in Lovecraft—the idea that the universe is full to the brim with life and sapience and that those things will outlast you and your troubles, and your species and its troubles, and probably your universe and its troubles. That there will still be someone around, exploring and creating and making new mistakes, long after everything you know has crumbled to atoms.

But it’s also a religion, followed by flawed and biased mortals of many species, and so I had a lot of fun with creating different interpretations and sects–the fact that Deep Ones and Yith and Outer Ones all worship Nyarlathotep doesn’t mean they all agree on Its nature or what It wants. And somehow, they all think the gods want them to do… the things they want to do.

What brought you from The Innsmouth Legacy books to The Fifth Power, your upcoming sci-fi novel about first contact?

The Fifth Power is completely different from the Innsmouth Legacy books, except that it includes snarky aliens, found family, and an obsession with large bodies of water. Style, I’m told, is what you can’t help doing.

First contact is one of my favorite story types—I’m fascinated by the idea of communicating across such a huge barrier, and the massive changes that would have to result from success. In addition to being a writer I’m also a cognitive psychologist, and I love thinking through what cognitive processes are necessary enough to be universal, and how alien thoughts would be shaped by their bodies and environments. I wanted to play with those ideas at novel length.

I also wanted to write an optimistic, plausible future for humanity. I love hopepunk and solarpunk, and the idea of offering something we can aim for. The Fifth Power is set at a time when we’ve “started to get it right,” and is in part about what happens when a governance structure set up to solve one enormous problem (in this case climate change) has to deal with a very different problem. I also harbor a superstitious hope that, much as Winter Tide turned out to be unexpectedly timely in some unpleasant ways, this one might turn out to be more positively timely.

The Fifth Power is in conversation with some other recent books, like Malka Older’s Infomocracy series, that posit new forms of government. I wanted to write about the thing that—paraphrasing Ursula Le Guin—is as different from late-stage capitalism as our current governance structures are from the divine right of kings. But I also thought about how the divine right of kings hasn’t entirely gone away, and what it looks like when the world is in the middle of one of those long, awkward transitions between methods of organizing society.

What’s your favorite cryptid?

Mothman—there’s no reason for it to be terrifying, because all it does is stare at you through your window. But it’s terrifying, because all it does is stare at you through your window! When I was a kid, I would keep the shades drawn tight after dark and refuse to look outside in case it was there. Mind you, I was perfectly willing to go outside on the porch. Mothman, as far as I could tell from books that it was kind of dumb to read after dark, would never confront you directly without a pane of glass in between.

Backup answer: The Aeslin mice from Seanan McGuire’s Incryptid series are awesome, and I would like a congregation to cheer me on.

What’s your favorite fantasy novel of all time?

I think it’s a tie between Katherine Addison’s The Goblin Emperor and Susanna Clarke’s Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell. The Goblin Emperor is one of my comfort reads, a book about kindness and goodness in the face of pressure against both, with language patterns I can sink into when I can’t read anything else. Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell is intense and clever and full of telling detail that takes my breath away, with footnotes full of glorious side story and back story and foreshadowing. It’s too heavy to bring on a train and too perfectly-formatted an object to read as an e-book, but absolutely perfect for when you’re stuck at home (for some reason) and want a single novel that you can just sink into for a few days.

When do you find time to write?

I wrote Winter Tide while my wife was pregnant and sleeping an extra two hours a night. With kids, the answer is usually “way too late at night,” except for the brief period when I had an hour-and-a-half train commute. In our current March Unending, unfortunately, I have no idea what time is or where to find it. If someone finds some, please let me know.

What’s the one thing you can’t live without in your writing life?

My wife is my alpha reader and worldbuilding tracker. She’s the only one who gets to read stories in progress, and has been urging me to write the next bit for as long as I’ve known her.

What advice would you give to an aspiring fantasy author?

I always feel very nervous about answering this sort of thing—despite liking to give advice in general, writing advice always feels somehow pretentious. So this may sound pretentious: writing includes both composting and gardening. You do things, you have experiences, and those experiences go into the compost and eventually feed into the garden of deliberately trying to create words. (Like I said, pretentious. Ask me on a different day and I’ll tell you how writing is like chess or cooking.)

Composting advice is really life advice. The more experiences you try—new foods, intro classes in weird skills, talking to different kinds of people—the better your brain gets at modeling how people act, and at coming up with details to describe a spell or a journey or a royal feast. Reading is important because it shows you how other people use their craft and what the conversation looks like. Experience gives you new things to contribute to that conversation.

For gardening, the most useful suggestion I can add to reading and writing is feedback. Beta readers, workshops, a good editor—it doesn’t have to be all of these (I’ve never been to a workshop), but some combination will tell you what strengths and weaknesses others see in your work, and help you practice doing better. This never stops happening—there are things I didn’t learn about structure until I worked through the Winter Tide draft with my genius editor at Tor.com (Carl Engle-Laird, whose editing style I once recognized from across a room by hearing a fellow author freaking out about his terrifyingly brilliant edit letter), and then new things I’ve learned with each subsequent book.

What subject or genre do you want to write about in the future?

I really want to do a space opera. I have a set of ideas bouncing around, but at the moment it’s all a grocery list of disconnected ideas, like:

sapient starships that only talk to a select few

company of interplanetary seed savers with the social dynamics of a theater troupe

more snarky aliens

cheese

I’m trying not to push too hard on it until I hand in the current book! (But I’m already getting kind of fond of my hyperdramatic seed savers and the exasperated ship’s handler who’s stuck carting them around.)

Head on over to r/Fantasy for the full AMA!

I beg to differ that Mothman is not terrifying, because he does a bit more then just stare in windows. He chases cars, attacks an ambulance, might have tried to steal a baby (poor, poor Linda Scarberry was so traumatized by her initial encounter that she saw him everywhere, and her solo sightings including the baby stealing attempt are unreliable), and definitely materialized inside a man’s bedroom to attack him psychically.

Hello, this question is for Carl Engle-Laird: WHEN IS THE NEXT INNSMOUTH LEGACY NOVEL COMING OUT?!

Author Emrys said in January that she had a direction she wanted to take Aphra and Co. in; so…?

Signed,

Sobbing Old Man Who Won’t See Many More Sunrises and Wants More Innsmouth Legacy Stories Before Cthulhu Finishes His Coup